NEWTON, Kansas (Mennonite Mission Network) – It was the summer of 1966, and Arlin and Maretta Buller were trying to plan ahead. They knew they wanted to get married. They knew they both wanted to continue their respective teaching careers. They also knew that Arlin needed to complete two years of military or government-approved voluntary service in the coming years. What they didn’t expect was a phone call, just fifty hours before their wedding ceremony, that would immediately bind all their plans together.

The call was from Mennonite Board of Missions (MBM, a predecessor agency of Mennonite Mission Network). Arlin and Maretta had been accepted for voluntary service as special education teachers at Frontier Boys Village outside of Colorado Springs, Colorado. The previous teachers were leaving by the end of the summer, and the fall semester was just a few weeks away. How soon could they start?

“[W]e had an abbreviated honeymoon,” recalled Maretta. “By midweek we were home; wrote all our ‘thank yous’ from the reception, packed up all the things we wanted to store and what we wanted to take with us, and the next Sunday, we were in Kansas on our way to Colorado for our volunteer assignment.”

Established in 1960 as a ministry of Rocky Mountain Mennonite Camp, Frontier Boys Village was a rehabilitation program for adolescent boys who had been classified as ‘delinquent’ by Colorado’s juvenile justice system. The camp was transferred to the MBM Health and Welfare Committee in 1965, which brought hundreds of voluntary service participants like Arlin and Maretta to serve with the program as teachers, facilitators and staff. The camp operated until 1978, when the property was sold, and the funds were used to found the Frontier Village Foundation (FVF).

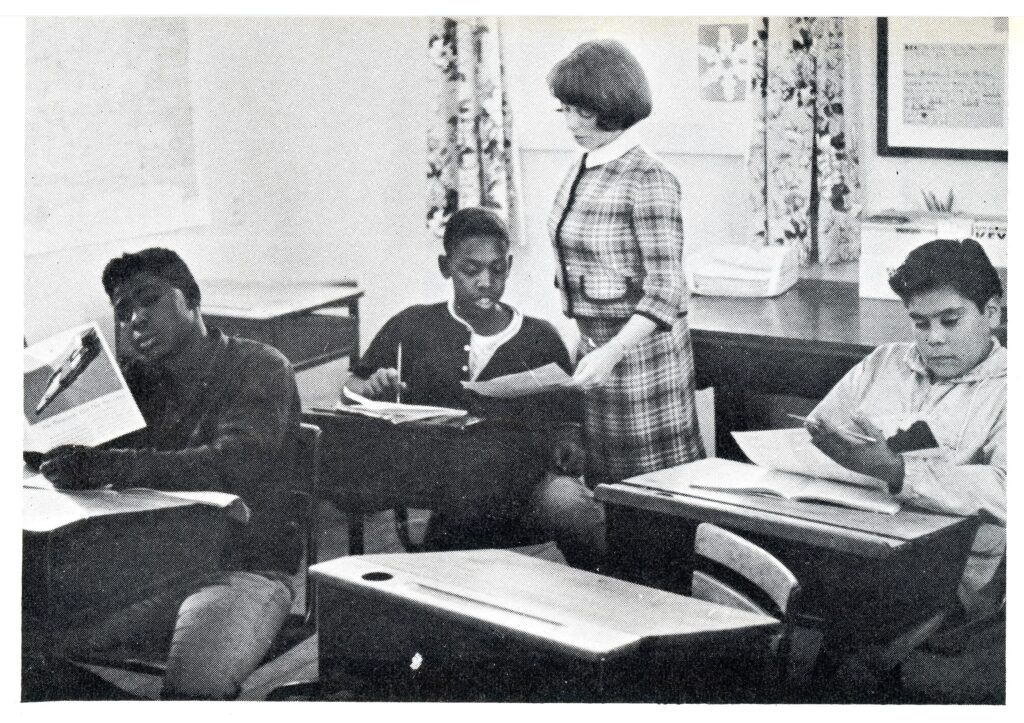

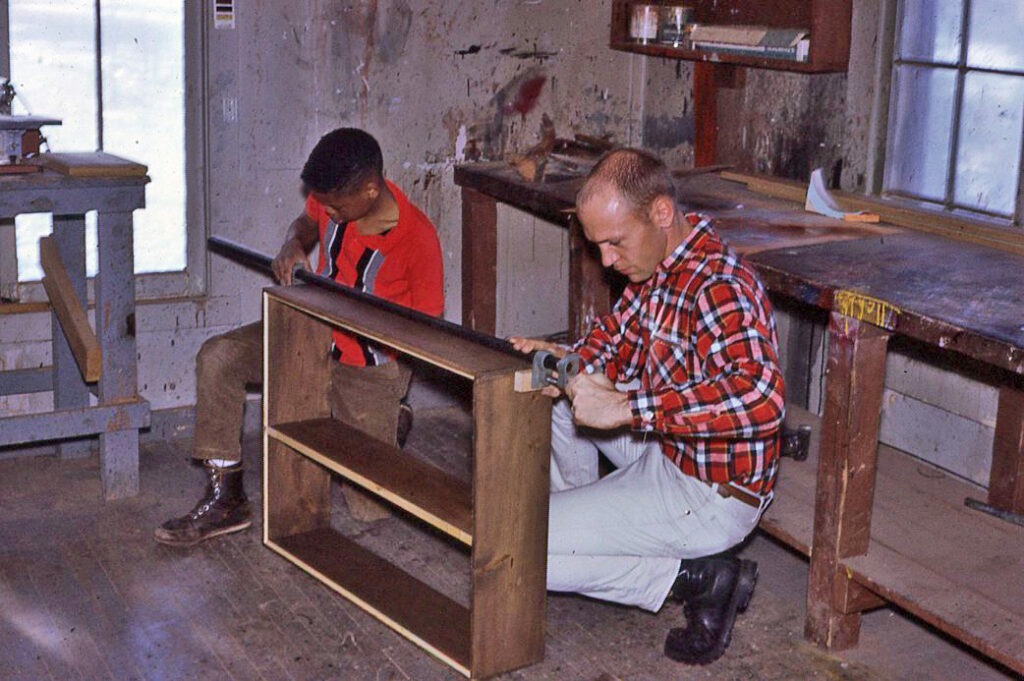

Maretta’s assigned role was teaching the elementary-aged boys, and Arlin taught the middle and high school ages, as well as shop and craft. Their teaching focused on strengthening subjects and skills that were often significantly behind the age levels of the students, usually stemming from an unaddressed emotional or learning issue, an unstable home life — or as was often the case — a combination of all three.

Arlin explained that the boys who had been labeled by the state as ‘delinquent’ and sent to Frontier Boys Village were just like other students he taught throughout his career in public schools, but their circumstances had made their lives particularly difficult.

“Delinquent kids are only just a little bit more normal than normal kids,” he said. “They’re no different than anybody else’s children. They’re the ones that got caught.”

The day-to-day work of teaching troubled children was stressful and rewarding in equal measure. The Bullers enjoyed success stories; boys who improved and grew through their classes, and they witnessed others who continued to struggle. Sometimes these stories were woven together. Years after their service, Maretta read a published letter to the editor of local newspaper detailing the conditions incarcerated people were enduring in a nearby prison. The author, she realized, was a former student at Frontier Boys Village, who was now writing on behalf of his fellow inmates from inside the prison. He had been elected to represent the group because of his skills in reading and writing.

After their two-year service term was completed, the Bullers went straight into graduate school, and then continued their careers as teachers.

When Arlin returned to a public school classroom after his service term, he found that his approach to teaching had fundamentally changed. The kids who acted out, who needed more attention, or a different style of teaching weren’t delinquent. Instead, they had “turned into average kids” who just needed a different approach to being taught.

“Those two years of working with kids who had been ‘caught’ gave me some impact with the kids that hadn’t been ‘caught,'” he said. “My perspective of my classroom was shaped by my experience with Frontier Boys village. And I would say, [it] enhanced my abilities.”

The couple acknowledged that their service experience was equally formative and difficult. Maretta summed up the sentiment though a phrase her father had used in describing his experience in Civilian Public Service (CPS) “The experience was worth a million dollars,” she said. “But I wouldn’t give you a quarter to do it again.”

Like the thousands of other conscientious objectors in the middle of the century, the motivation for Arlin and Maretta’s service participation was seeking an alternative to the U.S. government’s military draft. While Arlin knew that, as a teacher, he was not a prime draftee, he still had his two-year government service requirement “hanging over his shoulders” as he and Maretta worked to plan out a future together. Finding a service option on their own timeline removed that future variable, and neatly answered the question of where the couple — who had been teaching in separate states before they were married — would live for the immediate future.

While the cause for their service may have been a governmental requirement, the couple’s passion for the service they engaged in came from a much more personal place.

Maretta had been one of the two children at a CPS camp that her father served in as the business manager. Her grandfather had been one of the ‘seagoing cowboys‘ that volunteered after World War II to tend to the cattle on boats from the U.S. bound for war-ravaged Europe to replenish livestock herds. Arlin had heard stories and seen the yellowed photos of great uncles who had been detained during World War I because of their refusal to participate in military training. His father had been drafted during WWII but failed his physical.

“[Our] passion for service came from the stories we had heard as kids growing up,” Arlin said. Understanding how those stories connected to their families’ understanding of Jesus’ call to resist violence helped shape their decision to serve, even if they were too young to grasp the entire picture.

“I didn’t know the story like I know it now,” Arlin said. “But knowing part of the story helped shape my thinking. I think knowing the story is very, very important.”