"’You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’"

—Mark 12:28-34

"Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress."

—James 1:27

We have all been taught to love our neighbor as ourselves. We bring food to sick people, give money to worthy causes, and donate our time to serving our community. We want to make sure that we are living out Jesus’ commands. We care for those [who are] in distress. Yet, when we witness someone being harassed, it’s hard to know how to help. We’ve seen stories of people who tried to help, but their help escalated the situation, and so we stay quiet, unsure of what to do, unsure if it’s our place to step in, and unsure of how we are supposed to defend the defenseless.

For those of us who have been harassed, we wanted someone to defend us in that moment. We wished someone had stepped in and found a way to help us when we were vulnerable. This Bible study seeks to explore those questions and prepare us to be better neighbors. It seeks to show us how to defend modern-day orphans and widows.

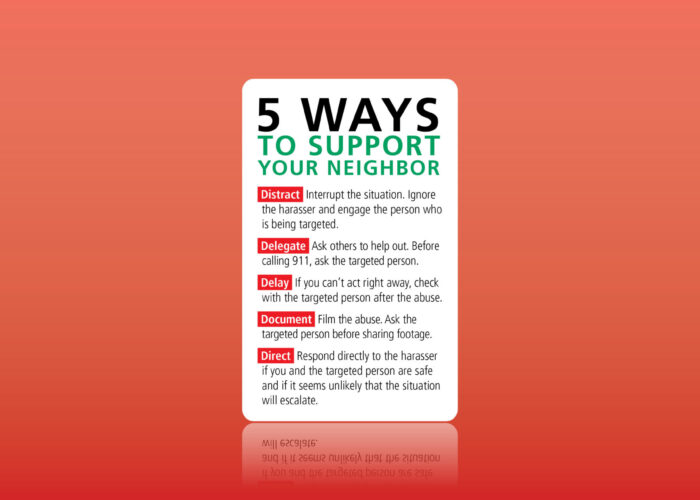

Bystander intervention steps into a situation to stop public harassment from continuing, or to provide care for someone who experienced public harassment. Bystander intervention allows individuals to send powerful messages about what is acceptable and expected behavior in our community. To do this, we need to develop a sense of who might be harassed, where harassment can happen, signs that someone is being harassed, and what actions might help that situation.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) recorded 1,372 separate incidences of bias-related harassment from Nov. 7, 2016, to Feb. 7, 2017.

1. Who are likely victims of harassment? Any [one who is a] member of a minority group or anyone who is perceived as lacking in power. Some examples of these groups are:

- Racial minorities (Asians, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Black people, etc.).

- People of differing religious backgrounds (Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, etc.).

- Sexual and gender minorities (lesbian, gay, transgender, gender nonconforming people, etc.).

- People of a lower socio-economic background (homeless people, those on government assistance).

- Women.

- Children.

- Those with mental and physical disabilities.

Each community is different and will have different populations of those who are likely to be victimized. Who do you imagine may be a victim of harassment in your area? It can be helpful to look up your specific community on the website link below so that you are better equipped to recognize harassment when it occurs.

SPLC provides a resource called Hate Watch, where the incidences are broken down by state. They also provide a resource called Hate Map that will give you an idea of the hate groups that have a known physical presence near you.

2. Where does harassment happen? The short answer is anywhere. Where it happens will depend largely on where you live. If you live in a big city, you may witness harassment on public transit. If you live in the country, you may witness harassment at a local store. But harassment can happen anywhere from schools and churches to public parks and sidewalks. This training will focus on public peer-to-peer harassment.

Other resources address police harassment, workplace harassment (boss to employee), and other types of harassment.

3. Signs someone is being harassed. Sometimes harassment is easy to spot: Someone is shouting verbal insults and belittling another loudly. Other times it can be subtler. It could be a gesture or a passing word. In those cases, it’s important to pay attention to body language. People will often recoil or take a defense posture with their shoulders slumped if they are being harassed.

4. Why is it important to intervene? Being harassed can be humiliating and traumatic. Even one person standing up and doing something helps the victim know that they are not alone, and can reduce the negative effects of trauma. If you are someone who is constantly being harassed, it can be easy to believe that people are mean, and you may want to go out. Your intervention reminds the person being harassed that they are a valued member of the community and that someone cares about them. It can, therefore, lessen the long-term effects of the harassment.

Principles for nonviolent engagement

Martin Luther King Jr. provided six principles of nonviolent engagement in times of public confrontation. Engaging these principles adds us to a long line of peace activists who engaged their faith in public.

1. Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people. As Christians, we see the full breadth of our life as an act of faith—how we eat, work, shop, and relate to the world.

2. Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding. As Christians, we open up ourselves to the surprising possibility of enemies becoming friends.

3. Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice, not people. We respond to others recognizing that every person is created in God’s image, and that every person can be healed of their hatred.

4. Nonviolence holds that suffering can educate and transform. We believe that God is at work to create communities to confront and end suffering through our nonviolent response to hatred.

5. Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate. Our prophetic anger toward injustice is always rooted in love for the other, even our enemies.

6. Nonviolence believes that God is on the side of justice. Throughout the Bible, we discover a God who comes to the vulnerable and the despised. When we are on the side of the oppressed, we are continuing to tell this story with our lives.

Small-group discussion

1. What have you heard that surprised you?

2. Have you ever witnessed harassment? If so, what was your response?

3. Have you ever been a victim of harassment? What did the people around