This story first appeared in Anabaptist Climate Collaborative’s

The Climate Pollinator newsletter.

On July 7 at

MennoCon23 Youth Climate Summit, experts in climate change, spiritual activism and social justice will explore ways that youth and young adults ages 14-25 can put their faith to work to address this crisis. It will be a day of worship, learning and collaboration. Youth sponsors are welcome to attend.

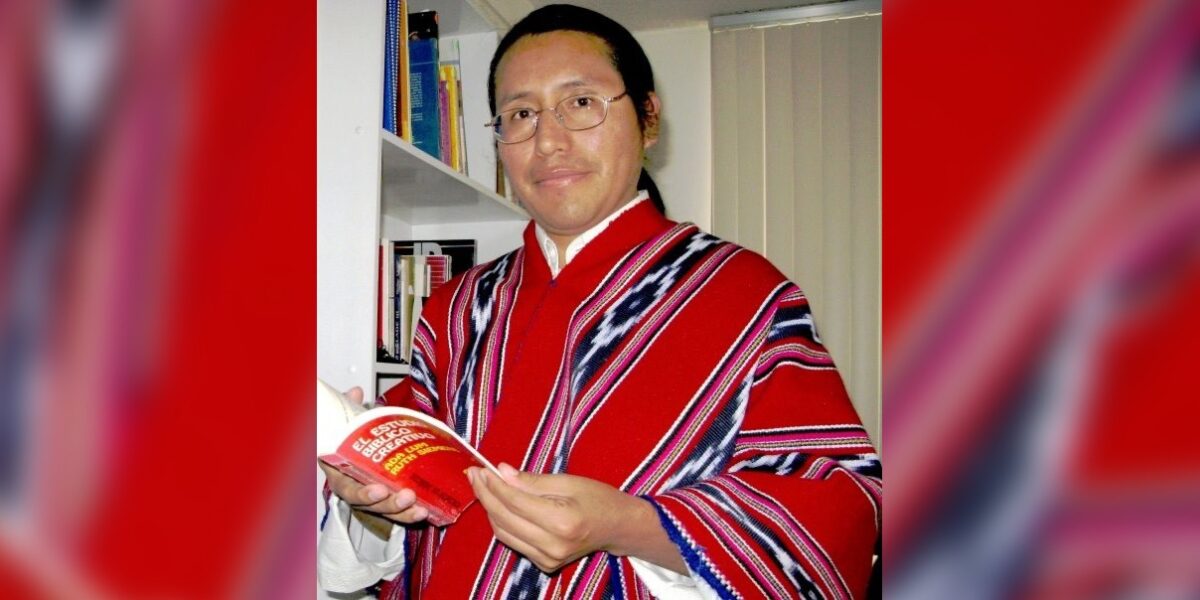

“I am a Kichwa, a speaker of the Kichwa language, from the province of Chimborazo.”

That is how Julián Guamán introduced himself. The secretary for

Iglesia Cristiana Menonita de Ecuador (ICME), an Indigenous conference in the process of joining Mennonite World Conference, Guamán chooses to identify as a Kichwa, and a Kichwa-speaker, because he believes the Indigenous Andean worldview is worth preserving, and sharing, especially in the face of climate change.

“Language is the reflection, or manifestation, of the worldview of a people.” Guamán said, “A person’s worldview forms the foundation for their relationships with other beings and with creation in general.”

Growing up in the shadow of Ecuador’s tallest volcano, Chimborazo, Guamán’s first language was Kichwa. When he began learning Spanish in elementary school, he said, “It was a deconstruction of my Kichwa world in an attempt to build a world in Spanish.”

Guamán, author of

FEINE, la organización de los indígenas evangélicos en Ecuador [FEINE is the Consejo de Pueblos y Organizaciones Indigenas Evangélicos del Ecuador (Council of Indigenous Evangelical Peoples & Organizations)] and Ph.D. student in Latin American studies at the

Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, sede Ecuador, explained the difference between the Spanish language of the

conquistadors who defeated the Incan empire and colonized most of the South American continent in the 1500s, and the Kichwa language, which can be traced back to the Incas and is spoken (in different dialects) by

8.4 million people throughout the South American Andes.

In Spanish, Guamán said, sentences begin with a subject — often a human being — acting on an object; either another person, or a non-human entity. Like most Western languages, Spanish portrays humans as separate from the natural world.

“This has tangible implications because if human beings have a worldview that puts them outside of the environment, they can objectify a tree, an animal, a bird, the minerals, the rocks, the river, the water, the air. They see them as objects: as tradable, as negotiable, as sellable, as buyable, as manipulatable, as controllable.”

By allowing people to see themselves as subjects dominating the world around them, Guamán said, “The structure of the language of the colonizers permits the exploitation of the land and the people.”

In Kichwa, on the other hand, sentences often begin with a predicate containing a verb. This is because action and interaction are of utmost importance. “There are less words that focus on the subject,” Guamán said, “and more words for describing action.”

Because nouns carry less weight in a sentence, they come later on. In addition, the way sentences are structured allows for the possibility of multiple subjects interacting with, instead of acting on, each other.

“The whole system and vocabulary [of the Kichwa language] is inclusive and seeks interdependence with the other,” Guamán said. “This forms the foundation for the Andean worldview that is based in parity, in relationship, in coexistence, in interaction, in harmony, in equilibrium.”

In South America, as around the world, people and land have been and continue to be exploited by a societal system built on Western worldviews. In the face of climate change, Julian believes that Indigenous languages offer an alternative way to understand and interact with the natural world that others would do well to learn from.

By choosing to speak, think and write in his native language, Guamán commits to this counter-cultural way of being in the world.