In spring 2023, Jennifer Murch joined a United States Civil Rights Just Peace Pilgrimage. In fall 2024, she spent two weeks on a Racial Justice Just Peace Pilgrimage to South Africa and blogged about her experience. This is her seventh and eighth blog from her pilgrimage, edited for length. You can find the original post on her blog. We will publish her blog series weekly for several weeks, so be sure to check back for more.

Day Nine

In South Africa, we were warned not to go out alone or at night.

“I’m on my 28th cell phone,” Steve Schallert, director of International Solidarity and one of our leaders, off-handedly told us. “Getting robbed is a part of life here. If someone robs you, just give them what they want. If you resist, stabbings are common.”

“Is it safe to run alone in the morning?” I asked.

“Yeah, probably,” he replied.

We had another paradigm-shifting contextual Bible study, one of Jesus’ parables about the Kingdom of Heaven.

In Matthew 22:1-14, a king hosts a wedding banquet, but the invited guests refuse to come. He then invites street people, yet expels one not dressed properly.

I wondered, what if the king was just a king? What if the people knew that the king’s invitation was more a display of force than one of kindness? And what if, when they were finally forced to participate, the one guy’s refusal to wear the proper party attire was simply an act of civil disobedience?

“But how is that showing us what the kingdom of God is like?” someone asked.

“Perhaps ushering in the kingdom of God is not necessarily fun or happy,” I replied. “Acts of Resistance can be ugly,” I said. “It sometimes ends in death.”

“Remember the context,” Steve said. “Jesus is telling this parable right before he goes to Jerusalem and is killed. Things are heating up and his stories are getting more political.”

“Who else remained silent when questioned by a political ruler?” someone asked. Oh right, yeah, we all nodded: Jesus.

And then Steve broke down the four dominant movements in Jesus’s day. These four groups were all Jewish, he said, and they all responded to the oppression differently.

- The Zealots practiced violent resistance.

- The Essenes withdrew completely and went into a “holy huddle.”

- The Herodians were collaborators. (Jesus’s ministry was financed by Herodians, women who worked in Herod’s palace and then diverted funds to Jesus.)

- The Pharisees were hard leftists who believed their liberation was dependent on right praxis.

“Which group are you in?” Steve asked. Nkosi said he’d be tempted to go with the Zealots. “Because what happens when you no longer have a cheek to give?”

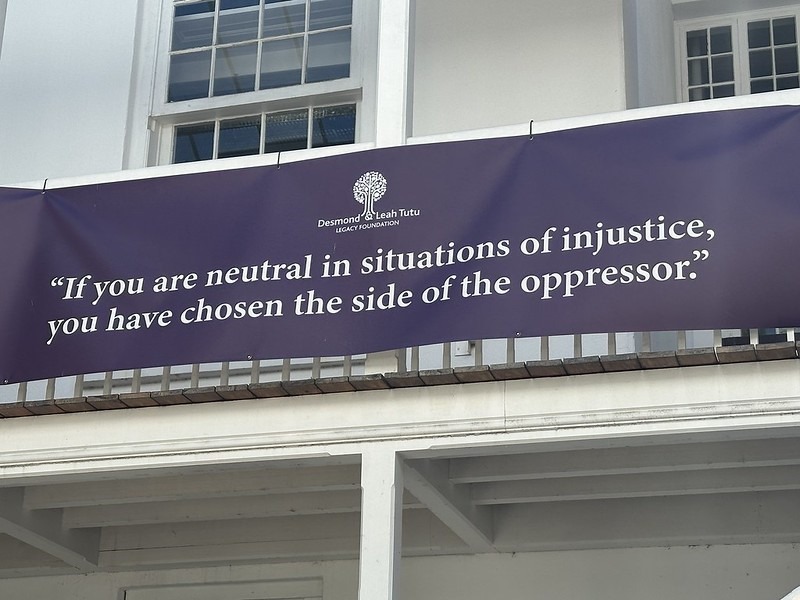

Later in the day, we visited the Desmond and Leah Tutu Exhibition in Cape Town. Desmond was a South African Anglican archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who fought against apartheid and for human rights. In the foyer is an art installation of a laughing Desmond flying through the air from a swinging chandelier. Andrew Suderman, Mission Network director of Global Partnerships, said that Desmond had played peekaboo with all three of Andrew’s children. He said it was hard to have a conversation with Desmond when children were around because he preferred to play with them.

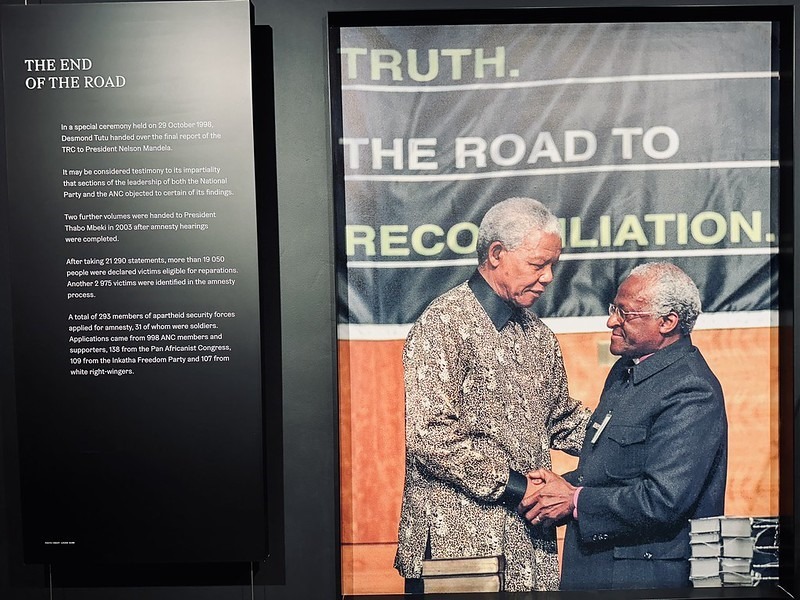

The museum was organized into six sections, each one explaining a different aspect of the Tutus’ life and work. One room was dedicated to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which was established in 1995 to address human rights violations during the apartheid era. Here, Nkosivumile Gola (Nkosi) and Buyisiwe Pokie Putu (Pokie), Iziko Lamaqabane, (the hosting organization) leaders, stood next to a display titled “The End of the Road” in which Tutu was handing the TRC’s final report to Nelson Mandela, former president of South Africa.

“That photo is revealing and problematic,” said Pokie. “What does it mean that the church is handing over its work to the government? And the TRC wasn’t the end of the road — not even close. There are many lingering problems and much more work to do.”

A film about the TRC was playing on a loop at the other end of the room, but our leaders refused to watch it. “I don’t want to be retraumatized,” Nkosi said. “They way they treated Winnie [Mandela’s wife], …,” Pokie shook her head.

“Maybe I shouldn’t watch it,” I said, explaining that I was worried that if the video’s story was skewed, then I might not have a good-enough grasp of South African history to be able to sort out the nuances.

No, no, watch it, they urged. Then we’ll talk.

When I rejoined them, they asked what I thought. I told them that the video made it seem like Winnie was guilty of torturing and killing people, and I thought it seemed strange that Tutu was practically begging her to apologize, because any religious leader ought to know better than to force an apology.

“According to the Mandela movie I watched before this trip,” I said, “it seems like Mandela divorced Winnie because she’d gotten too radicalized, too violent. In this movie, it was her fault that the marriage didn’t last.”

“Winnie challenged Mandela,” they said. “She understood the people. Mandela lost touch while he was in prison. Lots of people say he sold South Africa short.”

“Did you know,” Pokie said, “that even though Mandela remarried, it was still Winnie who took care of him when he was dying?”

“If they still loved each other, why did they divorce?”

“If Mandela was going to lead, he couldn’t be with Winnie,” said Pokie.

“Winnie had power and was dangerous for the government,” Nkosi said. “She got blamed for actions that she didn’t do — everyone knew there was no way she could’ve been present for them. She was a scapegoat.”

There is much I didn’t understand about South African history, but I was beginning to get the gist: as with any story, if you think it’s simple, then dig deeper and it’ll get complicated real fast.

After the museum, we picked up sandwiches from a bagel shop (chicken on a soft pretzel bagel) and then walked to a park for lunch and conversation, some of which I filmed.

Before you watch, a few things to be aware of:

I edited the conversation but also left in some of the pauses. From the beginning, Iziko told us they would move slowly, giving us time to absorb the information, and they provided that slowness in the daily schedule as well as the ways in which they guided our conversations.

You will hear Pokie responding to Nkosi with a deep “huh” or “umh,” a vocalization indicating that what the person was saying had hit home.

After lunch I called an Uber and rode to Muizenberg Beach. Then popped into a bakery for tea and an almond croissant.

According to Google maps, it was a 10-minute walk to Blue Bird Garage where our group was meeting up for supper. The map’s walking instructions were confusing, so I asked a young couple with a baby how to get there, and then, with the daylight fading, I set off at a brisk pace, all the while thinking of the warnings against walking alone.

As soon as I left the touristy beach and hit the main street, a woman dropped in step beside me. She said she was attending college and needed money for bus fare. No, sorry, I said, never once breaking stride. From the corner of my eye, I saw three men watching us from across the street, and then I noticed another man following behind us. For the duration of that walk, I was afraid. I kept moving, making a point not to give street signs more than a quick glance, and only when I turned the corner and spied people from our group, did I relax.

Day Ten

Morning talk turned to social change

Someone in our group mentioned that we gather strength from acting together — we don’t have to do hard things on our own — but I said that our need to do things as a group, to agree with the people we relate to, can be a tripping stone. Many times, acts of resistance are done by individuals, not communities. And since countering power isn’t exactly a pleasurable activity, waiting for a whole group to take action together might be foolish, especially when our social circles include the people with the power.

“The answers are not found in the voting booth,” Steve said. “It’s the day before election day and the day after that is our political act. I’ve done my stints in jail, and it was fun.” He grinned. “We sang a lot.”

We spent the afternoon on Chapman’s Peak where we were encouraged to write down events that stood out to us in the last couple weeks and note things we wanted to do when we returned to the States in order to link the two worlds and provide accountability for our future selves.

That evening we walked to a winery for supper.

Cape Town is loaded with vineyards and wineries. The common weekend culture is to climb a mountain, hit a beach and, then, relax at a winery.

At first, we were the only group in the dining room, and we were jolly-loud. After a White family of four sat at another table, someone pointed out that the older gentleman kept turning around in his chair and looking daggers at us.

In South Africa, it was explained, Black people are considered boisterous and loud while White people are calm and quiet. (These stereotypes exist in the US, too.) It didn’t matter that some of the White people in our group were louder than anybody in the restaurant, or that the topic at hand was a friendly theological debate, or that another White party had been seated in the same room and was whooping it up merrily. The fact that our group included some Black people meant that we were the problem. On his way out the door, the guy turned to our group, swore, and then snapped, “I hope you’re having a lovely evening,” before stomping out. So, there you have it: a snapshot of apartheid’s afterlife in all its glory!