In spring 2023, Jennifer Murch joined a United States Civil Rights Just Peace Pilgrimage. In fall 2024, she spent two weeks on a Racial Justice Just Peace Pilgrimage to South Africa and blogged about her experience. This is her first blog from her pilgrimage, edited for length. You can find the original post on her blog. We will publish her blog series weekly for several weeks, so be sure to check back for more.

Just Peace Pilgrimage is a program of Mennonite Mission Network. To learn more, including how you can join in a pilgrimage yourself or with a group, click here.

Day 1

Each day with Iziko Lamaqabane, the South Africa organization that is hosting our group, started with a contextual Bible study. The set-up was nice: comfortable chairs circling a woven mat scattered with photos, burning candles, incense, and other symbols of South African culture.

Iziko’s director, Mzwandile Nkutha, or Mzi (pronounced “em-ZEE”), asked us to share three things: What brought us? What did we hope to learn? And what gift did we bring?

What did I bring? For the last few months leading up to this trip, I’d battled low grade dread, anxiety and apprehension. There was the safety issue, of course — that was the easy one to fixate on. My younger brother spent one of his college semesters in South Africa and when he heard I was going, his first response was, “You know South Africa’s pretty dangerous, right?”

That morning, when it was my turn to speak to the third question, I said I wasn’t sure what I brought. “I’m a down-to-earth sort of person. I have lots of questions, and I’m often skeptical about things.”

Mzi said, “Jacques Derrida, a French philosopher, said, ‘Cynicism is an act of love.’ I think cynicism and skepticism are quite similar. Being skeptical can be an act of love.”

That statement hit me at my core. Here I was, a White woman in a Black country worried about getting “it” wrong, insecure about my ability to understand the depth of the issues, emotionally shaky. And yet when Mzi shared that quote, I suddenly felt seen. I felt valued. Mzi’s words were a gift, maybe even a blessing.

An absurdly abbreviated timeline of South Africa’s colonial history:

- 1488: Portuguese sailors arrive, and the South Africans chase them away. The Portuguese report that the South Africans are savages.

- 1652: The Dutch East India Company arrives. The South Africans don’t want them there, but the DEIC insist they are different. Fine, the South Africans say. Refuel and go on. But instead of leaving, the DEIC builds a castle/fortress. Then they build a second building — a slave quarters — and import slaves from all over the world.

- 1795: the British arrive. For the next 100 years or so, the British fight with the Dutch, the Dutch fight with the Zulus, etc.

- 1833: The British abolish slavery, in part because, thanks to the Industrial Revolution, there is a greater need for consumers rather than workers.

- 1887: Gold is discovered in the area that is now Johannesburg. At that point, there were only about 300 White people in that area, but only nine years after the discovery of gold, Johannesburg (Jo’burg), named after two White men named Johannes, had become a stronghold.

- 1901 Bubonic plague: Black people are blamed for it, thus providing an excuse to evict them.

- 1913: The Natives Land Act is passed which allows for segregation of land based on race.

- 1932: Orlando East, a settlement on the outskirts of Jo’burg for migrant gold workers, is formed. This is the beginning of Soweto, a.k.a. the Southwestern Township.

- 1948: The Dutch establish an apartheid government. Over the next few years, a total of 148 laws to keep Black people separate from White people are passed. South Africa’s apartheid government studied, and drew inspiration from, the United States’ Jim Crow laws.

- 1950: the Group Areas Act, the division of the country into areas (determined by the government) to separate people by race, is passed.

- 1953: Bantu Education, an inferior education for Black people, was formed.

- 1960s: The rise of the Black Consciousness Movement – a grass roots anti-apartheid movement that began in the late 1960s.

- 1976: A student uprising, in protest of the government’s directive that Afrikaans be the language of the schools, launches the horrors of apartheid onto the global stage, and intensifies the protest movements.

- 1994: Apartheid is abolished.

- 1996: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins to hold hearings.

Of all the Iziko leaders, Nkosivumile Gola (Nkosi) was the most reserved. He’d listen to the conversations, his hat and glasses obscuring his eyes, but when he spoke, it was like a fire hydrant had been turned on: his whole body would vibrate with energy, and the words would come rushing out, each phrase a verbal fist-punch.

For example:

“I am jealous of the South African story!” Nkosi said that first day, his words hard clipped. “Who gets to tell the story? It should be Black people telling the story, not White people!”

“I am speaking to you,” he continued, “in the language of the minority! And the minority can’t even bother to learn the language of the majority! Because the majority is invisible to them!”

It didn’t take me long to figure out that when Nkosi spoke, I’d better listen. Actually, that was true of all the Iziko leaders. But Nkosi, I found, was the most raw and unfiltered, the most edgy. He ran hot, and I adored him for it.

Day Two

After our morning’s contextual Bible study, we loaded into the bus and drove to our first site of struggle: Constitution Hill and the adjacent Prison Complex.

While we waited for our tour guide, our leaders pointed to the walkway running along the side of the courthouse. “See those women over there? They have been camping out for the last year in protest of the reparations that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission promised but did not deliver. Two of the women died over the winter because of the cold.” Almost immediately, a couple of people from our group wandered over to talk to them.

GBV = Gender-Based Violence

“What are they doing?” Buyisiwe Pokie Putu (Pokie), director of Afro Feminist-Womanist Solidarity, asked, when she realized what was happening. “Why are they going over there?”

“Should we go get them?” someone offered.

“No,” she said, frowning. “They’re already there.”

Later when Pokie told them they should not have gone over, they asked, “But don’t they want us to talk to them? They’re making a public statement.”

“Yes, but why would they want to talk to you? How will you help them? Who benefits by you talking to them? Those women are living their lives. Don’t interrupt them and make them tell their story to you. Why would you do that?”

This woman, I realized then, wasn’t going to coddle me. She was going to make me think and then rethink my thinking.

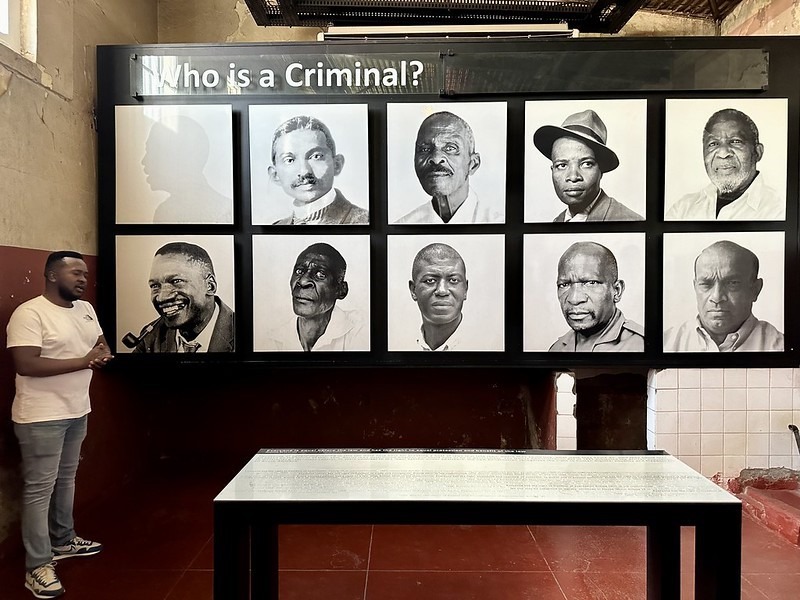

In the prison complex, we meandered through the rooms that housed the male prisoners, both political and criminal. When Nelson Mandela was held there, he was placed in the White section because they feared he’d start an uprising if they placed him in the Black section. He served four terms in this prison, more than seven months in total.

We read the testimonies and looked at the devices used to beat and torture the prisoners. We saw the small row of outdoor toilets and listened to the tour guide describe the indignities of the strip searches: in front of everyone the men were required to jump into the air and spin to give everyone a clear view of their genitalia.

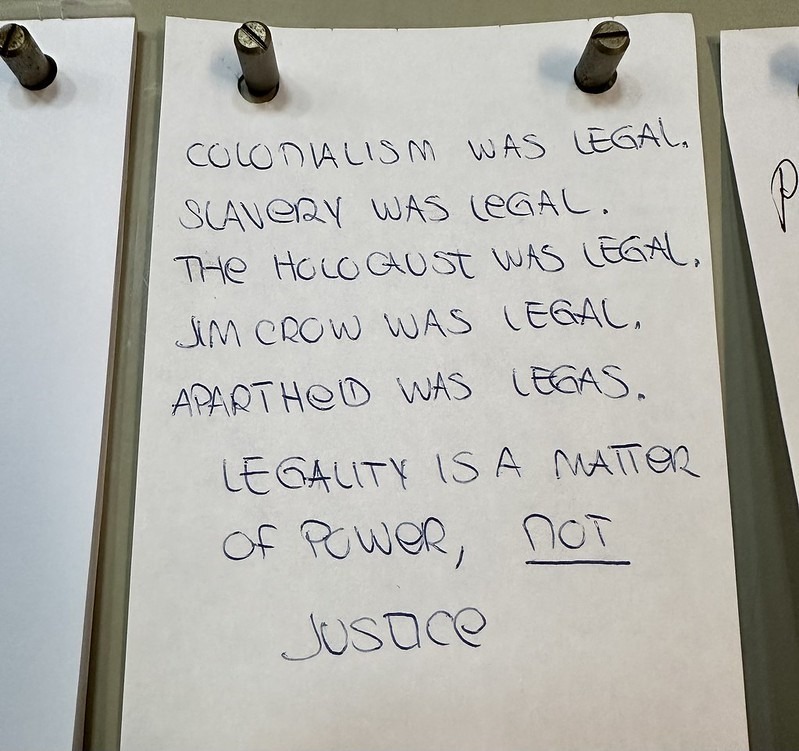

One of the notes a visitor to the prison left on a cell wall.

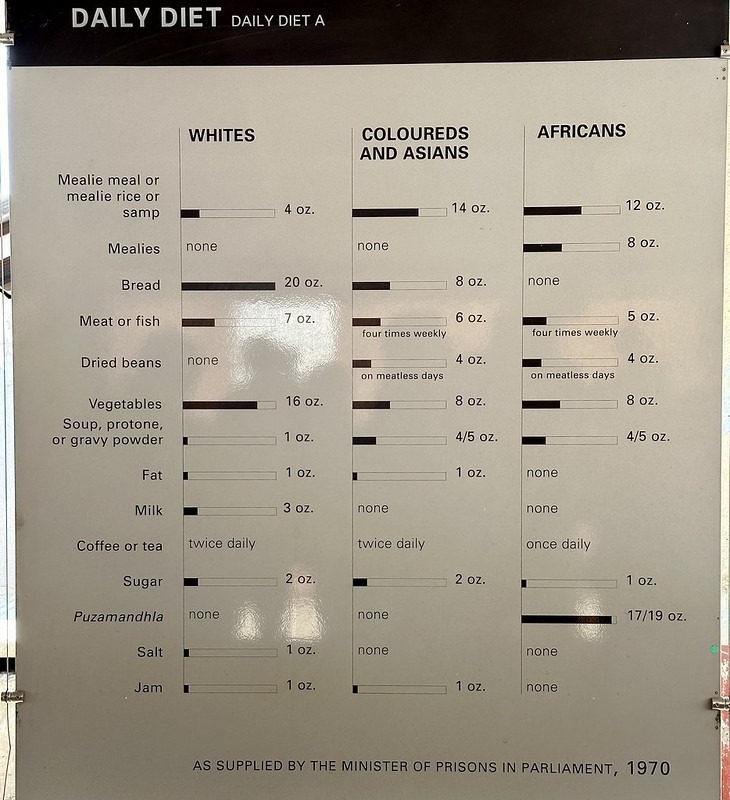

The prison was equipped to house 900 people, but it usually held about 2,000. The men were fed a sparse diet, and proportion size was based on race. They were allowed to wash their plates once every three months, and showers happened once a week, if that. Disease was rampant.

In the back of the prison was the row of isolation cells.

Prisoners were held there for up to thirty days and often fed a diet of rice water — water that had been used to wash the rice prior to cooking.

From there, we crossed the patio to South Africa’s Constitutional Court. The building, which was inaugurated in 2004, was designed to specifically counter the atrocities of apartheid and is rich with symbolism, all of it pointing to openness, light, and accessibility, a government for all the people.

For example, on the outside of the building, the phrase “Constitutional Court” is written in the twelve national languages, one of which is sign language. Inside the spacious foyer, light floods in through huge floor-to-ceiling windows. Clusters of metal “leaves” stretch from pillars that list like giant tree trunks. Slits in the ceiling allow natural light to filter down. Benches, and wooden “stumps” are arranged in clusters. At the entrance to the courtroom, there’s a sign listing all the upcoming cases, open to the public, and a TV mounted on the foyer wall plays when the court is in session so that anyone may watch. In the corner of the foyer, one of the former prison guard towers remains, built into the building as a reminder of what had been at that location before.

Afterward, I walked down the long interior hallway.

On one side was an art gallery, and on the other side were large windows that looked out over the protesting women’s encampment. There was one picture that caught my eye: a giant naked manbaby, sleeping. The label read:

“The struggle by many White South Africans to face up to the exploitation and abuse of Africa and its people is explored. Sleeping, in Kentridge’s work, is a metaphor for a state of ignorance, a return to the imaginary, which conveniently allows the external world to be forgotten. However, the sleeper must always wake up.”

And then, back into the bus for the 30–45-minute drive to Soweto, a large suburb that was first started in the late 1920s to house the migrant gold mine workers.

There is one road into Soweto, and there is a military base at the start of it — if there was an uprising in Soweto, the police barricaded the street to contain the unrest.

When we arrived in Kliptown, an informal settlement within Soweto, George Ranaka, our tour guide, greeted us and then led us into the Freedom Charter Memorial.

Inside the concrete tower, he explained each of the ten clauses inscribed in a huge concrete table. These clauses had been drafted by the South African Congress Alliance in 1955, and as George explained them — equal human rights for all, the people will share in the country’s wealth, the people will govern and work and security for all — were some of the clauses.

When George finished, three young men entered the memorial to sing for us. “Young people don’t have many ways to earn money here,” George said, “so they get creative.”

George led us out of the memorial, across a road, and up on a bridge that overlooked Kliptown.

As a 40-year resident of Kliptown, George knew well the complicated logistics of getting medical attention, the annual flooding that resulted from being situated in the marshlands, the overcrowded housing and sanitation issues. He told us about the children’s program he works for, and how they provide food to dozens of children, as well as educational and emotional support. “We have the Freedom Charter,” he said, “but this is our reality.”

On the bus out of Kliptown, I asked Pokie how the South African people, in the face of such extreme poverty and racial injustice, keep from being bitter? How does it not eat them up inside? Emotionally speaking, how do they manage it all?

“We have this word: ubuntu,” Pokie said. “Ubuntu means generosity or hospitality. It’s how we approach each other, with an attitude that says, “Your needs are as important as mine.’”

Steve Schallert, director of International Solidarity, who had flown in from Cape Town earlier in the day, was in charge of our evening debriefing.

Some snippets of our conversation…

“The work of resistance,” Steve said, “is the deconstruction of civility.” Because who gets to say who is civil and who’s not?

“But I recently read that Margaret Mead said that the first sign of civility was the discovery of a broken femur that had been healed,” someone countered. “It seems to me that civility is a good thing.”

But is it? The mission to civilize has destroyed civilizations, someone else pointed out. And what’s the difference between modernity and civility? Or development and civility? All of these “good” words we use, Steve argued, words like develop and civilize and modern, are colonizer language, rooted in a colonial mindset, and deeply problematic.

“Civil society” is government in society, Steve said. In South Africa’s case, it’s the White people, the colonizers, who have decided who is civil and who is not. We decide whether or not we will negotiate with someone based on if they are sufficiently civil according to our standards, our White colonizer standards.

“I am not represented here,” Nkosi said, flailing his arms wide. By “here,” I gathered that he was implying everything in our physical setting — the buildings, the infrastructure, the educational system, the whole structure of South African society, all of which had been built by the White colonialists. “This is my country and yet I am alienated everywhere I go.”

Round and round the conversation went. Turns out, it’s hard to see our “good” language from a different perspective — a colonizer perspective.