In spring 2023, Jennifer Murch joined a United States Civil Rights Just Peace Pilgrimage. In fall 2024, she spent two weeks on a Racial Justice Just Peace Pilgrimage to South Africa and blogged about her experience. This is her seventh and eighth blog from her pilgrimage, edited for length. You can find the original post on her blog. We will publish her blog series weekly for several weeks, so be sure to check back for more.

Day Seven

Steve Schallert, director of International Solidarity, split us into small groups to read that morning’s scripture — the Parable of the Talents — but before we dug in, he said, “I want you to ask yourselves how is this parable a parable of resistance? Read it through that lens.”

Summary of Matthew 25:14-30:

- A master provides each of his servants a different number of talents (a single talent is 20 years’ worth of wages) based on their abilities and then leaves.

- The first servant invests the five talents he was given and doubles the amount, and the second servant, who was given two talents, does the same. But the third servant, who was given just one talent, buries it in the ground.

- When the master returns, he praises the first two servants, but he is angry with the third servant. “You should’ve invested it”, he says, and then he gives the man’s single talent to the first servant and casts the unprofitable servant into the darkness.

I’d been taught that this parable was about using our God-given gifts in whatever measure we’ve been granted to do good in the world. But listening to the parable that morning I was struck with an entirely different meaning. It was so wildly different that when Buyisiwe Pokie Putu (Pokie), an Iziko Lamaqabane, (the hosting organization) leader asked us what we thought it meant, I hesitated to share.

“We’re brainstorming,” Pokie said. “There are no wrong ideas.”

“I don’t think the master is God,” I said.” I think the master is a master. And the servant who buries his talent is refusing to participate in the master’s system. Perhaps by burying the talent, he’s opting for contentment instead of accumulation? Maybe contentment is an act of resistance?”

Turns out, my gut reaction wasn’t far from the mark. When Steve called the whole group back together, almost everyone had reached similar conclusions: that third servant was refusing to participate in a system of death by keeping the money out of circulation.

“But can’t a parable have more than one meaning?” someone asked.

“Of course,” Steve said.

“So, it can still be about using your gifts wisely?”

“Sure,” Steve said, “but that’s not what this parable is about. If you think this parable is a story about using your God-given gifts, then you’re taking it out of context and turning it into colonialist theology.”

Steve explained, “If I read myself into the narrative, then as a white, cisgendered man from the United States, I am the colonialist. I am the master. The Bible isn’t written for us” — he waved his arms to indicate our group and himself, and grinned — “at least not directly.”

Capitalism says that righteousness is the multiplication of talents.” he said. “Apartheid was a Christian movement using exploitative labor to sanctify capitalism. Apartheid theology is slaveholder theology. We must ask ourselves who are we reading the Bible with? When we talk about good stewardship, what is the system to which we are being stewards?”

Suddenly, a parable that had always seemed meaningless to me felt nothing short of revolutionary. It had power.

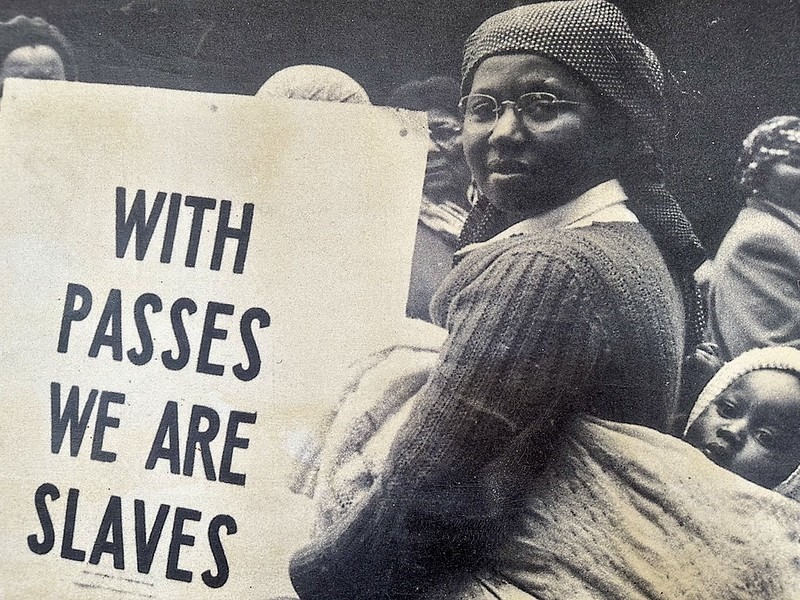

Later, at Langa, one of Cape Town’s informal settlements, we toured Langa Dompas Museum. The buildings used to house the offices of the Bantu Affairs Administration which issued the dreaded “pass” which Africans had to carry in “White” areas under apartheid. It was a criminal offence not to have a valid pass.

In 1954, men and women gathered in Langa to protest the pass laws, and out of that gathering, the women’s movement was formed. Less than a year later, 20,000 women staged a march to protest the pass laws and meet with the Prime Minister. He wasn’t there when they arrived, so they left petitions with more than 100,000 signatures for him and then stood silently for thirty minutes, hands raised in an open-palmed salute.

From there we went to the District Six Museum which commemorated a community which had been razed during apartheid, the people forcibly removed to different neighborhoods according to the race they’d been assigned.

Before we went into the museum, we were met on the street by Reverend Rene August, a student and close friend of Desmond Tutu. She told us the story of the District Six street signs.

When organizers had first planned to build a museum, they issued a request for memorabilia from District Six. Not long after, one of the organizers received an anonymous call. “I’m the one who gave the order for the bulldozers to begin destruction,” said a man’s voice. “I have something to show you — I think you’ll want it for the museum — but I will not give you my name. I will pick you up to take you to see the items, but you cannot see my face.”

Even though this organizer had been jailed and tortured during apartheid, he allowed himself to be blindfolded and seated into a car. When they arrived at the location, the nameless man opened a garage door revealing dozens of street signs from District Six. He explained that after the first day of razing, he’d picked up one of the street signs and took it home with him, even though it was illegal. From then on, collecting the signs became an obsession. Now he was turning them over to the museum.

On the museum floor was a large map of District Six as it had been before it was destroyed. When the museum first opened, people flooded into the building, dropped to their knees, and began writing themselves into the map. After a few years, the museum put a second layer on top of the floor map to keep it protected.

An elderly woman gave us a tour of the museum. She’d been a child when the forced removals happened. One of the hardest things for her was losing her beloved doll. But then, just a few years back, some people began unearthing artifacts (illegally, I think) and uncovered her doll. Nearly 60 years after the demolitions, her doll was returned to her. “I feel complete now,” she said.

After the museum, Rene led us up the street to the original site of District Six.

It’s just a barren field now, “a scar to remind us of what happened here.”

Day Eight

In the Bo-Kaap, a Muslim community in the heart of Cape Town, we learned that this neighborhood had been the only area in the city center that was never named a “White-only” area during apartheid.

The city government wanted to build a bridge to racially divide the neighborhood, but because officials hesitated to destroy religious buildings and the Bo-Kaap had ten mosques, they never did it.

There were Palestinian flags everywhere, as well as lots of pro-Gaza graffiti. We’d seen this same messaging in Jo’burg. South Africans, we learned, are deeply attuned to the Palestinian situation. In fact, just a week or so before we’d arrived in the country, Steve had helped organize a march in Cape Town to protest the genocide and nearly 90,000 people showed up.

It makes sense that South Africans would be so proactive with what’s happening in Palestine: once a person’s lived under an apartheid government, it’s all too easy to identify one when you see it.