Kwanzaa is an African American holiday that is celebrated Dec. 26 – Jan. 1. Its creator,

Dr. Maulana Karenga, developed the holiday after the

Watts Uprising of 1965 in Los Angeles, California.

I use the term “uprising” intentionally, instead of the colloquial term “riot.” A riot implies rampant chaos and destruction without aim or purpose (i.e., property damage, looting and physical harm). Whereas, what happened in the Black neighborhoods of Los Angeles was a direct response to the oppressive social conditions that Black residents had been experiencing for decades. People weren’t just aimlessly wreaking havoc. There was a coordinated effort to send a message and make change. Was there looting, property damage and loss of life? Yes. However, strategy was also employed, pain was expressed, and self-determination was sought. As a result, the terms “rebellion” or “uprising” feel more appropriate than “riot.” During the Watts Uprising, more than 30 people were killed, 1,032 were injured and more than 3,400 were arrested.

The spark that ignited the uprising was the arrests of Marquette, Ronald and Rena Frye after a traffic stop. A fight broke out between the Fryes and the officers who were trying to detain them, and as the community gathered to bear witness, tensions boiled over. After decades of unequal housing conditions, lack of access to adequate employment and police brutality, people were fed up. It’s easy to read about the Watts Uprising and wonder how this could have happened. Fortunately, we have some insight to pull from.

Speaking to an audience two years after the Watts Uprising, Martin Luther King Jr. said this:

“…a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality and humanity.”

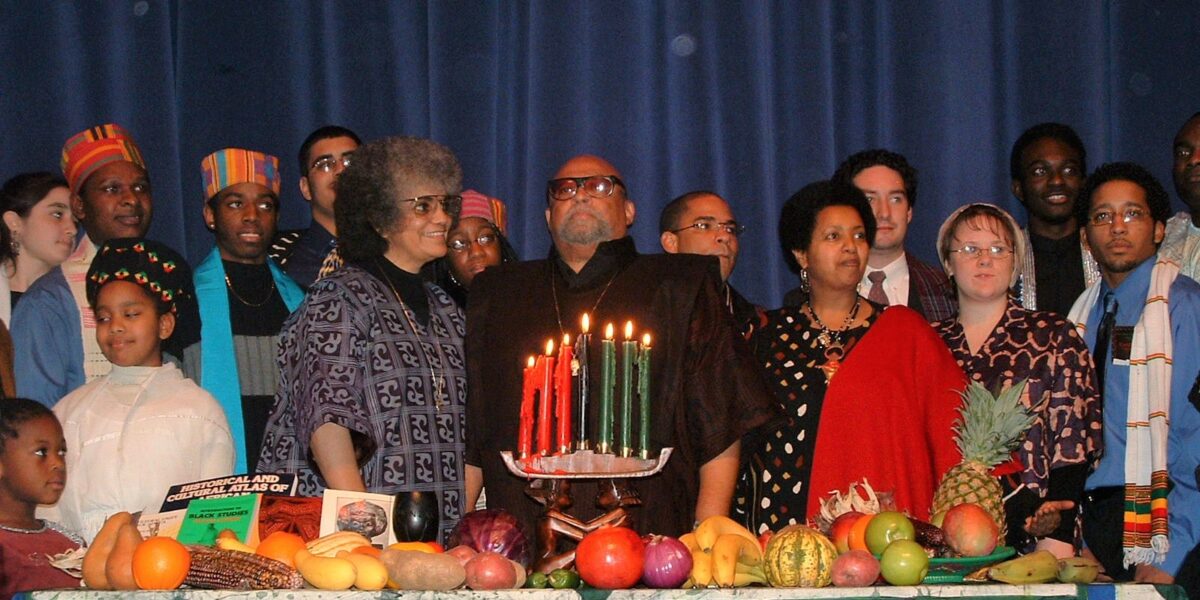

The Watts Uprising was a call for White America to listen. It was in the aftermath of these events that Kwanzaa was created. The week-long celebration is grounded in seven key principles, referred to by their Swahili names:

- Umoja (unity)

- Kujichagulia (self-determination)

- Ujima (collective work and responsibility)

- Ujamaa (cooperative economics)

- Nia (purpose)

- Kumba (creativity)

- Imani (faith)

On the surface, each of these values seems important, but taken within the context of the African American experience in the United States, they become even more powerful.

Unity becomes an invitation to collaborate for our freedom. Self-determination becomes the aspiration that drives us forward. Collective work and responsibility are the practices that keep us connected and remind us that, together, we can solve any problem. Cooperative economics allows us to circumvent capitalist systems designed to starve us. Purpose reminds us that our communities are far richer than we are led to believe. Creativity becomes the engine that makes way for our liberation, and faith is the foundation that ties us to our ancestors and life itself.

As we live into these values and celebrate our past, present, and future during the final week of the year, we remember how remarkable our communities are. Kwanzaa is an African American response to systemic injustice — a week-long invitation to honor ourselves and a reminder of the power we have in community.

Can people who aren’t part of the African diaspora celebrate Kwanzaa? I don’t know that there is a universal answer to this question.

Personally, I think everyone can honor the values of the holiday without celebrating it the same way that members of the African American community might by going to a community Kwanzaa event. If someone invites you over for dinner during Kwanzaa, accept the invitation. Identify Black-owned businesses to buy from during this season. These are all acceptable ways to join in the spirit of Kwanzaa and, thus, acknowledge all that this week represents for the Black community.

Additional resource