Originally published on January 22, 2020, this blog by Edith and Neill von Gunten reflects a reality in 1966 that is still prevalent today and has become more apparent during the ensuing months of 2020. As Martin Luther King, Jr. day approaches, read this blog and reflect on Dr. King’s legacy as he said, "Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’"

Even before our wedding in 1965, we had

decided to spend the first years of our marriage in Mennonite Voluntary Service

(MVS). Several units were suggested to us; we chose to go to the inner-city

unit at the Woodlawn Mennonite Church in southside Chicago. It was a decision

that completely changed the course of our lives.

The Woodlawn congregation felt

strongly that it was their role to speak out on justice issues and to get

involved. Opportunities for involvement were often shared before the Sunday

morning service ended.

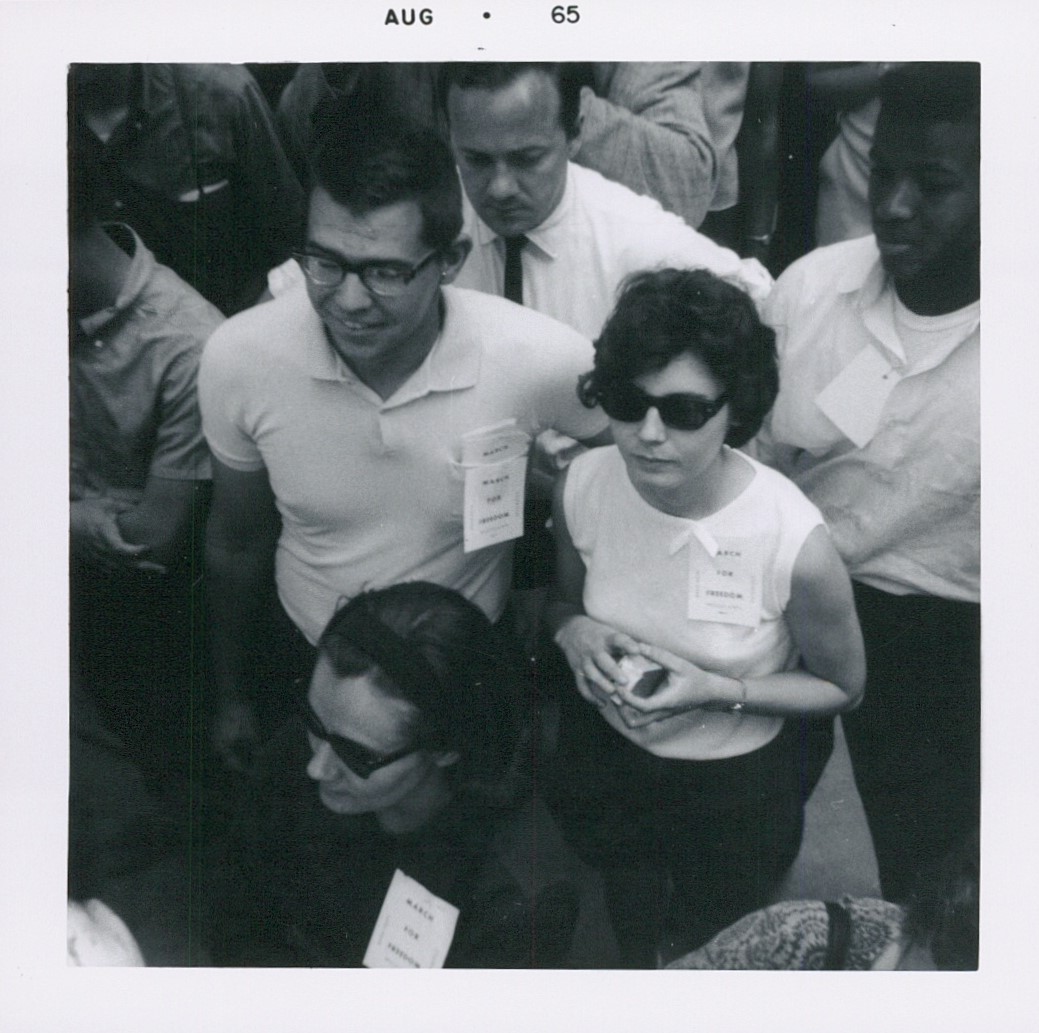

Woodlawn Mennonite Church pastor Delton and Marian Franz can be seen in the center of this picture of the Chicago march. Photo by Neill von Gunten.

As we began to really listen to the

people we lived and worked with, we started to understand how pervasive racism was.

As we heard the stories and experiences of people in the community, we came to know

more about their reality and ongoing issues.

These were the years of the civil

rights movement in the United States. Soon after we joined MVS, Martin Luther

King, Jr. was invited to come to Chicago to bring the racism and prejudice of

the north to light. Both of us, along with other VSers, Woodlawn church members,

and thousands of others joined together in marches through downtown Chicago

(often from Buckingham Fountain to City Hall) and in rallies.

Most of the marches were peaceful,

but once the marches spread beyond downtown and the Black neighborhoods, it was

a different story. Here is one example that Neill experienced while protesting

the housing discrimination in some neighborhoods in the city.

Dr. King’s entourage sent two couples into the Chicago Lawn – Gage Park area, a

lower middle-class neighborhood in the city’s southwest side, on the pretext of

renting an apartment. The area’s population was largely made up of

working-class eastern Europeans who lived in bungalows and for generations were

predominately Irish Catholic. One couple sent there was Caucasian with little

education, and the other was a well-educated African-American couple. The

Caucasian couple was given several choices to rent; the African-American couple

was given no options.

As a result, Dr. King and his

delegation organized a march through Gage Park on Aug. 5, 1966, to highlight

this disparity. Dr. King had orders for the

assembled crowd before the march began. We were to look forward at all times.

We were never to look into someone’s eyes during the march because we could set

them off on a tirade. We could not chew gum. Women were to be put in the

middle, with men on the outside. If we could not refrain from violence when confronted

by people watching, we were to leave and not participate. He did not want us

there if we could not follow these orders.

Dr. King was struck by a rock thrown

by a taunting mob as he was leaving his car — a sign of the violence that would

happen that afternoon. Thankfully, he was not hurt too badly and, after being cared

for, came to the front of the line to finish leading the march, with police

right by his side. He was understandably shaken and told newsmen that he had

never been met with "such hostility, such hate, anywhere in my life."

The night-stick wielding police

estimated that there were approximately 7,000 of us there to march that day. We

were ridiculed, sworn at, called all kinds of names, and spat on. Children spewed

the same hate as the parent next to them as we walked past their house. Some

carried Confederate flags. Signs were common: "N***** Go Home,"

"Wallace for President," "KKK Forever," "White Power,"

"Wallace in ’68," "Washington D.C. is a Jungle — Save What is

Left of Chicago."

We were told that when the march ended at Marquette Park, there were about 3,000

police officers to watch us. As the Caucasian crowd of men, women and children

grew and tried to confront us physically, the police surrounded us marchers to

protect us from what had become a mob throwing cherry bombs (exploding

firecrackers), stones and bricks — in addition to their slurs and insults. I was

ashamed to be Caucasian!

As this chaos swirled around us, we

waited for the rented buses to pick us up and take us all back home. When the

buses finally arrived, the bus drivers needed full police protection to get

through to us. For a moment, I felt safe on the bus, but I was wrong! We had to

stop at a red light before leaving that neighborhood and a group of about 50 youth

and men rocked our bus and tried to get at us inside. Someone threw a brick

through the bus window and hit a man in the seat in front of me in the head,

giving him a large gash. The rest of us yelled at the bus driver to go through

the red light to get us out of there. It was not until we got into the African-American

area that we felt safe.

After the march, we regrouped, and Dr.

King spoke to the gathered crowd. He had been hit with a brick on the back of

his head during the march. I remember him saying then — as well as many other

times — that we must forgive our Caucasian brothers and sisters because they do

not know what they are doing. They were taught that hatred, and now we needed

to show them forgiveness and not fight back, he said. That is the only thing

that can make them stop and think.

Another photo of the civil rights march in Chicago, 1966. Photo by Neill von Gunten. |

Those two years with MVS in Chicago

made us question the role of the church in “real life:” We witnessed the

unfairness of the political process in the United States in regard to its

neediest residents.

The desire to learn more about how we

as Christians could affect change and work with people in marginal situations

influenced our education after MVS, as well as our decision to live alongside

indigenous communities bordering Lake Winnipeg. We served there in a pastoral

and community development role for 36 years before becoming the co-directors of

the Native Ministry program for Mennonite Church Canada.

As you can probably imagine, we have

many stories of our MVS time in Chicago that made an impact on our life — way too many to include

in this reflection!