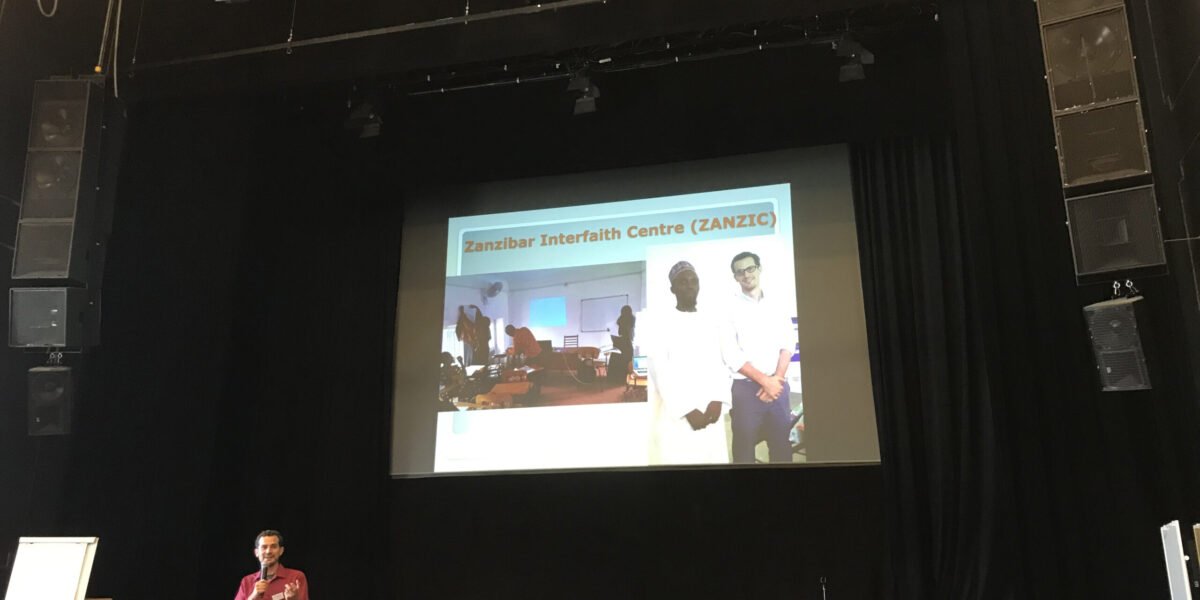

Peter Sensenig currently serves in Chad through Eastern Mennonite Missions and Mennonite Mission Network. From 2015-2020, he worked with the Zanzibar Interfaith Center, which partners with DanMission, a mission organization based in Denmark. Through these connections, he received an invitation from the Danish Mission Council and its development agency, the Center for Church-Based Development-CKU, to lead seminars in Denmark and Sweden.

About 60 members of the Danish Mission Council and Center for Church-Based Development-CKU, attended the seminars I led on faith-based peacebuilding, May 13-16. Many of the attendees work in advisory and consultant roles with their partners around the world, Danish participants came from both the state church and the free church, and others came from Cameroon, Mali and Tanzania, among other places in Africa, as well as from Palestine and Southeast Asia.

Peacebuilding seminars in Denmark

At the request of the seminar organizers, I led three sessions.

The first one was on the biblical basis of peacebuilding, with the guiding question being, How do we ground our peacebuilding activities in Scripture?

Reflections included:

- Do we find a vision for peacemaking in the Old Testament?

- How does Jesus talk about peacemaking in his teachings? What can we learn about peacemaking through Jesus life and death?

- How does our theology shape our identity, and what role does identity play in peacemaking?

The second session focused on peacemaking values, skills and practices, based on these questions:

- What is moral imagination i.e., how can we think outside the box to find answers to ethical problems, and how can new ways of thinking shape how we approach peacemaking?

- How is managing conflict different from transforming it? How do we analyze a conflict?

- What values, skills and practices are necessary for conflict transformation?

Multi-faith peacebuilding, specifically in the context of Muslim-Christian relationships, was the topic of the third session, in which we:

- Examined incarnational hospitality: Where do we or our mission partners function as hosts, and where do we function as guests? What difference does this make in our peacemaking approach?

- Discussed the

SEKAP scale of Muslim-Christian relationships, which starts with syncretic interaction, at one end of the spectrum, and goes to polemical interaction, at the other. Syncretic interaction dismisses religious differences by supposing that all religions are essentially the same. While polemical interaction seeks to destroy all religions but ones own. The more moderate positions include existential interaction, kerygmatic interaction and apologetic interaction. Kerygma (which means proclamation in Greek) is to share Gods good news about the hope that is found in Jesus, while recognizing that there is much of Gods truth in Islam. - Shared stories of multi-faith peacebuilding from Chad, Ethiopia and Kenya.

We closed the seminars with personal reflections and sharing. I was impressed with how deeply the participants engaged with subjects, like the tension between justice and peace in situations, like Gaza. But many participants agreed that the Bibles emphasis on peacebuilding should shape our theology, as well as our approach to mission and development.

I was also interviewed by the Danish Mission Council.

Read the Q&A.

Panel of experts address Swedish students

A separate engagement that was organized by my hosts was at

Lund University, across the channel, in Sweden. I joined a panel in the political science department, which also included a long-time Swedish diplomat and a United Nations consultant. This was a very different audience than the one at the Denmark seminar. The 50 students were not oriented toward a religious worldview. Here, I spoke about my journey of working with peace and conflict in Somaliland, Zanzibar and Chad, and shared stories of what multi-faith peacebuilding work looks like on the ground. I encouraged them not to lose their sense of creativity and idealism, or moral imagination. I shared how my faith gave me hope for building networks of relationships, even with those who could be enemies.

The students asked many questions. One young woman asked for career advice. I gave a two-point answer:

- Do what you love, not what will make you lots of money.

- Spend time in Africa, because it will expand your view of what is possible.

Afterward, I was approached by two young men who wanted to talk further. They invited me out for coffee and told me how their military service had destroyed their sense of hope for the future. They saw armed conflict with Russia not as a matter of if but of when. They are bound to their terms of service and can be called up at any time. I lamented their loss of hope with them and can only wish that they will find deeper meaning in Jesus, the Messiah. In the absence of faith, trying to build peace is a lonely, uphill battle against cynicism and realpolitik, a governing system based on the practical rather than moral considerations.

Future opportunities for interfaith peacebuilding

This summer, I will be at the Zanzibar Interfaith Center for the first time since we left in 2020. While there, I hope to encourage the work weve established. Other opportunities also emerged from these gatherings for the chance to do multi-faith peace work in northern Cameroon and Abuja, Nigeria.

Some of the participants were also able to update me on the status of the Program for Christian-Muslim Relations in Africa and its French-language counterpart. This network will be of mutual benefit for Chadians and members of Shalom Seminary in NDjamena, where I teach.